| |

The Cherry Orchard

at the Phoenix February 2000

Set at the

turn of last century, Chekhov's play presents the juxtapostion between

past and present, tradition and progress, stagnation and change. Michael

Cacoyannis gives us a cinematic interpretaion of the original that

deals thoughtfully with these universal themes.

Anja (Tushka Bergen) travels to Paris to collect her mother, Madame

Lyubov Ranevsky (Charlotte Rampling), who has decided to return to

the family estate in Russia after a disastrous love affair. She arrives

home to find the famous cherry orchard in full bloom, but the finances

of the estate on the verge of ruin. Thus Lyubov and her brother Gaev

(Alan Bates) find themselves scrabbling to retain a vision of gentility

amidst a climate of huge social and economic transition. Almost childlike

in their unwavering belief that what has always been can never change,

they are trusting and generous but completely ill-equipped for reality.

Meanwhile the younger generation must break out of the claustrophobic

grip of this nostalgia, to build a future far away from the delapidated

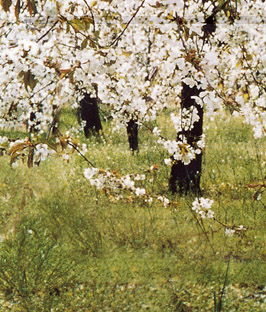

house and estate. The blossoming cherry orchard itself comes to symbolise

their predicament, a place of stifling and transient beauty where

Trofimov (Andrew Howard), the young tutor, gets caught in the branches

and the heady heavy scent lulls the family into a false sense of security.

From a visual perspective, the film captures the setting for the drama

perfectly. The crumbling wooden mansion, a haven of decaying wealth

where the lustre of rich furnishings has long disappeared, and where

the servants struggle to retain the facade of order while everything

around them disintegrates. The cherry orchard is a beautiful flurry

of white, yet the cameras also convey that crucial sense of claustrophobia,

the ominous tranquillity of the orchard and the cruelty of the branches

beneath the blossoms. The dresses of Lyubov, once splendid, are depressingly

off-white and the fur trimmings moth-eaten and bedraggled. Even Yasha

(Gerard Butler), the self-proclaimed valet, manages to create a more

convincing veneer of elegance in his cheap suits.

Charlotte Rampling is a fragile Lyobov, and her particular talent

for melodrama fits the character's stylised reactions perfectly. Alan

Bates is a deeply impractical, eccentric and kindly Gaev, obsessed

with billiard angles and existing in an unreal world of philosophy

and dreams. Meanwhile the rest of the family and the servants circulate

around these two, caught in the spell while it lasts. Melanie Lynskey

is a flirtatious Dynyasha the maid, while Frances De La Tour gives

an idiosycratic and rather creepy performance as the governess Charlotta.

Mention too, must be made of Michael Gough as Feers, the deaf servant

who mutters his way through the film, a bent old man who, we realise,

is a true relic of a nobler and more elegant time.

The director Michael Cacoyannis is keen to state that his film is

not 'filmed theatre'. I would disagree, as there is hardly a way to

avoid the theatrical roots of the story. The plot rests on the tension

between the characters, and the moral, spiritual and psychological

conflicts behind the dialogues. Once the setting is established, it

is the backdrop for all the action - the nature of the plot is such

that we cannot get away from the orchard and the estate. As a result

the film, while skilfully produced and masterfully acted, becomes

inevitably lengthy and claustrophobic. The level of involvement with

the same characters is almost unbroken and subsequently requires the

kind of concentration usually allocated to the theatre. Having said

all that, the ending of the film is effective enough to regain any

attention that might have been lapsing.

As a thought provoking piece of drama, this film is well-worth a watch,

but take supplies...

Jane Labous

04/02/2000

|