A regular in Oxford's literary sphere, poet and author Leatrice has had a busy few years. Her work has earned her spots as a featured poet for the Oxford Di-Verse Festival and the Oxford Indie Book Fair, a top 10 place for the 2024 London Independent Story Prize, and the winning submission for GRAVY's winter poetry prize, to name but a few. Now, ahead of the debut of her first poetry collection, she speaks to Daily Information about the voice behind the verse, and the restorative power of embracing cringe as much as nostalgia.

Daily Information: The collection is called Yearbook Signing, something that of course hearkens back to school days, memory and old or lost connections. What drew you to this particular framing?

Leatrice: I’ll say up front that I have a strong long-term autobiographical memory, which means my short-term memorization is terrible, but events and entire days or weeks play on a loop in my head. That makes it very difficult to forget, and therefore move on, from people. While I felt quite ashamed of my memory for most of my young adulthood, I started to notice how everyone wants to be remembered to some extent, and how they try to preserve their impact on the world. If not statues, awards, engravings, journal entries or archives, the basic act of signing someone’s yearbook or inscribing a book is like a time capsule. And the poems are also time capsules of moments I cannot forget but have at least made peace with.

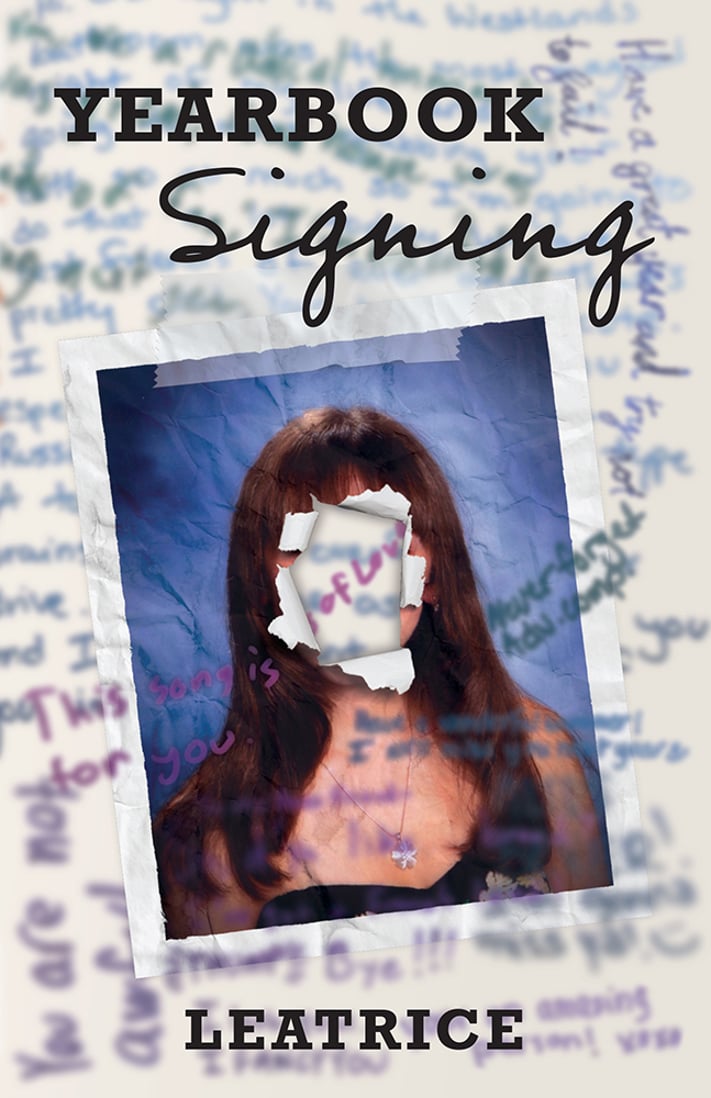

I have to thank my editor, Sebastian “Baz” Lewis, for suggesting the working title, Year in Review. For a little while that’s what it was called, but as I put the collection together, edited old poems and became more invested in the project, that title felt quite academic and dry. I wasn’t just “reviewing” the years and the relationships that colored them; I was reliving them. Baz agreed that Year in Review wasn’t quite right, and added that it suggested the collection would only apply to one year when it spans 20 years. Yearbook Signing implies annual revisitation. Plus, it immediately sparked ideas for a chaotic, expressive front cover.

DI: What was your writing process like for the collection?

L: It began with “Apocalypse Year”, which I wrote in 2022. Originally one poem in three parts, I realized I had too much to say about each moment and split them up. Each one is based on a year when humanity thought, or at least flirted with the idea, that the world would end: 2006, 2012, and 2022. They’re poems about endings, about feeling robbed of closure and salvaging whatever memories I can to make sense of what happened. That act of scraping and trying to explain the past was the spark.

Fast forward to 2024, when I threw every love/heartbreak poem I’d written into a word document for a casual editing session with Baz. I’d heard of a poetry pamphlet call from a small indie press (not my current publisher) and figured I could put something together in time. After the editing sesh, it was clear I had a lot of work to do, particularly on the older poems, but also that it was a project worth taking seriously. There were little patterns and tendencies I hadn’t noticed that made some poems impenetrable to a reader, while others were solid but needed some refinement. So I started editing the 20-something poems based on both Baz’s feedback and notes I’d taken from Oxford Writing Circle feedback nights over the years.

Then there was another submission call for books, but this was for collections. The key difference between a pamphlet and collection is length: pamphlets are usually up to 30 poems, while collections are over 40. This call required a minimum of 48 poems, so I opened up my first proper creative writing notebook and flipped through pages of cringe, looking for anything that could fit (with some heavy editing) to bring my poem count up. This act of swallowing cringe, of facing my younger self head-on and giving her words a new life, felt like forgiveness.

So, even though I was rejected from both submission calls (and many more), I kept editing. Most nights, whenever I was winding down from work, I’d edit the poems well into the early morning. I put together a playlist, in which each song corresponds to each poem, so that I could play a specific song on a loop until I was immersed in my former self, in whatever moment I wanted to write about. Something would click, and I’d rework the poem. If I was stuck, I’d just re-read the poem and remember the moment, sit with it for a while. In some cases, I tried my best not to re-traumatize myself.

Then I started writing new poems. I wasn’t trying to bulk the collection up to meet minimum requirements. Instead, I felt the need to patch up holes in the timeline. The collection is chronological, and some threads didn’t feel complete. For example, I wrote “Vivo in Spe (2025)” last April, and “The Walk from Grand Central to the Met is 40 Blocks” in May when I was visiting home. “Thud” is probably the most recent addition, as of September or so, and maybe a sign that I should play with form/shape in the future…maybe.

After a second editing session with Baz (in which I got to see Bournemouth at its peak over the August bank holiday), I spent the next day over-caffeinated, overhauling the collection. I let myself play with it, walk through the memories I used to wish would leave me alone. Eventually, it was ready to publish.

DI: You’re a regular with the Oxford Writing Circle and the Oxford Poetry Library; what impact have the city’s poetry and writing collectives had on your work both here and in general?

L: I’ll say it at every chance I get: they’re the reason this collection exists. I joined OWC in 2018 when I was heartbroken, in a rut, trying to focus on my master’s degree, and needed an outlet for creative writing. Their feedback nights were and are invaluable for anyone who’s just starting out, particularly for fiction/prose. Everyone is so constructive and kind, and some of my best friends in Oxford are from OWC. Then there are the writing prompt nights, the legendary literary quizzes, and the Authors Anonymous feedback sessions in which someone else reads your work aloud. I’ve not been able to attend for a while now, but the beauty of the group is its consistency. You can come and go, but when you return—whether to share something or just to listen—you’ll be exposed to some excellent writing and imaginative ideas.

I got involved in OPL because one of my OWC friends gathered a group of us to attend This is Just to Say, the monthly spoken word night, in September 2023. Spoken word is not my forté at all, and I still feel quite stiff reading my own work, but the environment was so wholesome and there was very little pretense. It wasn’t until May 2024, when I performed the “I Can’t Say It” series, that I was invited to post-event drinks at the Jolly Farmers with the other regulars. I felt validated, and began to cultivate another group of friends who had a distinct love for poetry that I had let rust. It was through OPL I started to notice poems, their technique, their sound, and most importantly, their heart. I attended workshops on performance, drafting, and even workshop facilitation so I could run my own about revisiting and revising cringey drafts from adolescence (which took place in Feb of 2025). I participated in the first-ever Poetry Bake Off (and am waiting for the next one). By the end of 2024, I was asked to be a featured reader at the Oxford Di-Verse Poetry Festival, where I met Yearbook Signing’s publisher, Reconnecting Rainbows.

Now, I’m starting to engage in more writing-related events around Oxford. I was a featured reader at the Oxford Indie Book Fair, thanks to Oxford Brookes Poetry, which was a wonderful opportunity. And I’m making an effort to attend the Sunday morning writing sessions at the Lamb and Flag, run by The Writing Well. I’d like to run my workshop again sometime soon, especially now that I have the collection; I have proof that braving the cringe works!

Ultimately, it’s incredible what people can inspire, what ambition they can ignite, by just believing in you.

DI:Who would you say your biggest literary influences are?

L: Fyodor Dostoevsky, Leontia Flynn, John Boyle O’Reilly, and Anna Akhmatova are the big ones. Also, albeit not a major literary influence on me, I do pay him homage in one of the poems, so I have to thank Nathaniel Hawthorne.

DI: As the writer, it’s obviously hard to pick, but do you have a favourite poem from the collection, and if so, why?

L: This IS a difficult question. If I can pick two, “Embrace” and “Eve on the Jubilee Line” encapsulate the whole collection. I also barely edited them, compared to others in the collection, so I’m particularly proud of them.

“Embrace” is about redemption and reconciliation. All the resentment, heartbreak and bitterness from earlier in the collection is gone, and you’re left with a poem in the middle of a conversation, refusing to say goodbye but unsure of what else to say. That’s the feeling, right there — the fear of being forgotten, of completely moving on after this person has had such an impact on your life. You’ve made your amends, you’re both significantly different people that for whatever reason cannot see each other as often as you used to, so what does goodbye mean now? How much do you want it to mean?

Embrace

Before I go, I want to tell you that

my friends own a wooden dining table

that believes in kintsugi.

Someone was able

to interrupt the grain

with azure sea glass

that weaves through each plank,

knitting what’s been done and undone

and we’ve done this

over and over and never again

but it’s so different

when you insist that you play no part

in how I should feel.

When your hand apologises to my spine,

I’m convinced we’re healing.

You should know, as I know now,

as you sleepily swerve home,

and Eldorado echoes across the Long Island Sound,

and we erupt like broken sprinklers

only once we’re alone,

there has never been anything other than this.

“Eve on the Jubilee” is a fun one. Imagine Eve and Adam are out in the world, riven with guilt over committing original sin. They are dangerous together, and they know it, so for the greater good they cannot reunite. That doesn’t stop Eve from wondering about him, which can be innocent, of course; I wonder about estranged friends, whether certain buildings are still standing, etc. But wondering becomes fantasy, then delusion. The poem is a warning, and there’s a reason it’s in the section about revisitation (“Graphite”). For all the intense feelings memories cue up, all the reminiscence that the collection seems to condone, we can’t get carried away.

Also, it's an almost-sonnet. It’s technically 14 lines but one of them is split in half. So the poem is just aching and yearning all over.

Eve on the Jubilee Line

I miss you like a missed connection,

a false flag in the crowd,

a name misheard, hissed and choked out

as the tube doors separate again.

That gasp, that scooping ‘hi!’

the words that tumbled us to bed,

the overripe, rotten, gnawed to shreds.

But would you really never?

Can I use words like ‘for good’

or are you always ‘for now’?

And if we ruin again,

what then?

What if it’s worth the waited while?

Eden never fell. We are just in exile.

DI: Describe Yearbook Signing in 5 words.

L: Unashamed nostalgia in 52 poems.

Yearbook Signing is available for pre-order from Reconnecting Rainbows Press. Curio Bookshop will be hosting a launch event for the collection on Wed 14th Jan featuring live performances from local writers and copies available to purchase.