A British citizen, Robert Liversidge, was arrested and imprisoned in Brixton Prison in wartime 1940 under Regulation 18B, one plank of sweeping security measures introduced as panic about German saboteurs and fifth columnists seized the country. This provision allowed the Home Secretary to detain a British subject indefinitely and without charges, based only upon its assertion that the detainee had "hostile associations." This case was eventually heard by five very senior judges sitting in the House of Lords.

This is the premise of Regulation 18B - No Free Man by American lawyer Scott Wright that played at Magdalen College in front of a 75-strong audience on Friday. A 3-hander, it explores an imaginary visit by one of the judges, Lord Wright (no relation) to the home of his long-standing colleague and friend, the now elderly Lord Atkin who lives with his daughter, in order to persuade him that his dissent from his four colleagues who are backing the executive's position, will give succour to Britain's enemies and besmirch his own reputation.

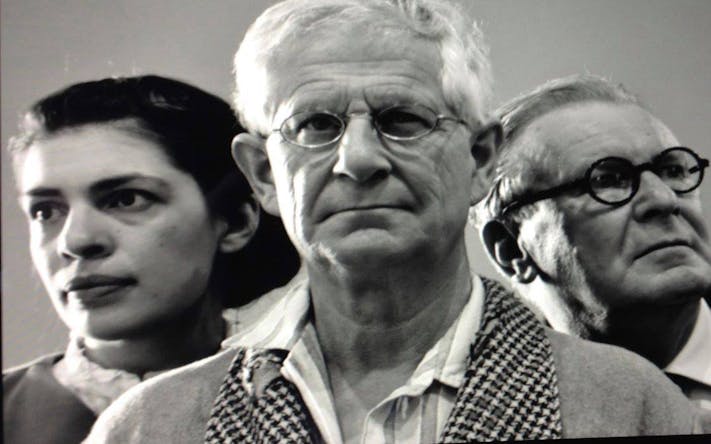

The raison d'etre of this short play is to explore the status of individual liberty in a time of war. Lord Atkin, preparing a blistering dissent, is determined to defend a long-held British legal right dating back to Magna Carta and the concept of habeas corpus. Putting aside its important content, what about Regulation 18B taken as drama? The mood in the theatre was, I think, very positive, but I had reservations. It took a surprisingly longish 30 minutes of worthy exposition, domestic chit-chat (neither especially interesting nor especially amusing) and character-establishment by Lord Atkin and his daughter (the smoothly-spoken and easy-moving Jess Hadleigh, making the most of the part), we finally came to the arrival of Lord Wright, though even then there were conversational niceties to negotiate before we arrived at the heart of the Liversidge matter. Even then, I was expecting a subtle debate between the two men on the concept of individual liberty, the duty of the state in time of war, and the ethics of mounting dissent in a time of patriotic crisis. These issues were touched on, certainly, but not really explored, and indeed Lord Wright's 11th hour intervention was revealed as having for its principal purpose a plea for his old pal not to ruin his reputation by rocking the boat in tempore belli.

Where I had no reservation, however, was in applauding the creative team. In the naturalistic, book-lined study of a set, the World War 2 sound design, and the way director Sylvia Wimpenny managed by use of movement and domestic detail in injecting life and energy into what might have been pretty static material. This was an amateur theatre production of first-class quality. Of our legal brains, Peter Pearson's Lord Atkin, all convincing Welsh accent, shuffling gait and impassioned argument, was matched sentence for sentence by Jeremy Radburn's Lord Wright, affectionately exasperated and equally forceful. Both were terrific.

The play was followed by a panel Q/A session, the respondents being four well-known lawyers. It was a pity that many of the questions put were inaudible to half of the audience. That glitch apart, I noted that our experts were all boxing out of the libertarian left/human rights corner and consequently were singing from the same song sheet. Producer John Castell explained to me afterwards that attempts made in the past to obtain a politician to join the panel had been fruitless. Nevertheless, while it's entirely legitimate and of course time-honoured practice for a drama-documentary to take up a polemical position, isn't it a little odd that in a quasi-debate by lawyers, particularly in a university setting, the prosecution should have a free run while the other side case goes unheard? I was put in mind of Mr Jaggers' excoriating the clientele of 'The Three Jolly Bargemen' in Great Expectations for poring over a newspaper report of a sensational trial and determining an accused guilty before the defence barrister had even stood up on his hind legs.

That said, food for thought aplenty was served up, notably in a reminder of the vital concept of no detention without reasonable cause by Malcolm Fowler, a solicitor advocate from the Black Country, by Lionel Blackburn who pointed out that the whole concept of a state of war was being redefined in our post-Cold War times, and by solicitor Alastair Logan who spoke about the discrepancy between the British government's tendency to lecture others on human rights while a number of its own practices can bear little close examination.