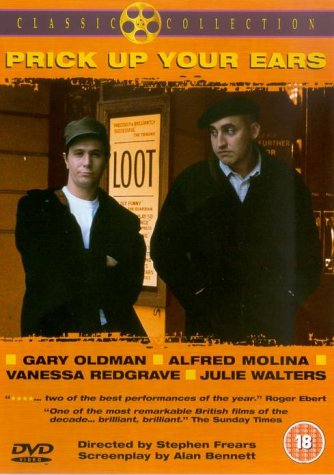

What a sly movie this is. And what a clever screenplay by Alan Bennett. For those who know nothing about Orton either as playwright or gay icon, the story is contained within the framing device of John Lahr seeking material to produce his critical biography of Orton’s life, also called ‘Prick Up Your Ears’ (1978). Lahr is impersonated in a wonderfully nasal and unappealing performance by Wallace Shawn who gives the distinct impression of being on the make as a literary grifter, gradually getting under the skin of Vanessa Redgrave’s flirtatious and commanding Peggy Ramsay. Ramsay is shown removing (stealing) the diaries from the Orton/Halliwell bedsit and presenting them to Lahr as personal booty, but only once Lahr has passed muster on whatever private scheme of vetting she employs. Bennett draws a parallel between the friction in the collaborative relationship of Orton and Halliwell and that of Lahr and his wife (a nicely judged put-upon Lindsay Duncan). There’s a lovely scene in which she and Leonie Barnett (Joe’s sister, a vivacious turn from Frances Barber who shows that the Orton family wit and earthy humour was not confined to Joe) warm to each other in a frank exchange about men and their sexual habits. Every actor is spot on – Julie Walters as Mrs Orton, Richard Wilson as the prison psychiatrist – , but the mischievous mimicry of Oldman as Orton is uncanny, whilst Alfred Molina brings unsettling depth to the failing mental health of Halliwell.

On the big screen the Moroccan sequence glows with brightness and the montage of Orton/Halliwell’s arrival at the beach in Marrakech gleefully sends up the equivalent moment in ‘Some Like It Hot’ – right down to the use of the same music. Other delights more appreciated on the big screen are the colour palette - all grim and grainy - showing the London of Orton’s cottaging expeditions and the sequences shot in the exterior of Neville Road, the rain lashing down on Paul McCartney’s Rolls Royce come to collect Orton for a discussion of the doomed screenplay, ‘Up Against It’.

A word on Lahr’s treatment of the ‘Diaries’ and Bennett’s screenplay. On the level of literary biography, Lahr’s editing of and interpretation of the Diaries need a further reinvention thirty years down the line, and the screenplay is a further barrier that needs unpicking. It may be a given that all art selects and arranges its components to best present a narrative, and from contingency derive meaning, but Bennett is complicit in Lahr’s reading of Orton’s lifestyle, even as he takes a dig at Lahr through his device of the parallelism of the ignored partner. The (in)famous cottaging orgy scene (Saturday 4 March, 1967), which is shown in the film out of its chronological order as an adjunct to Orton’s success on the night of the Evening Standard Awards, is deliberately placed in the ‘Diaries’ as a literary joke in opposition to a disastrous trip to Morocco. Morocco is meant to symbolise sexual freedom in contrast to the dangerous and squalid sexual cottaging of 1960s London. Orton jets off on a sudden holiday only to face disaster and lack of sexual achievement at every turn. He returns to a triumphantly-written orgy in a lavatory on the Holloway Road. The diary entry ends with a quip from Halliwell which is the punch-line to an extended literary joke – “It sounds as though eightpence and a bus down the Holloway Road was more interesting than £200 and a plane to Tripoli” – but that literary gag cannot be pulled off on screen, or is dropped by Bennett and Frears in favour of a story which depicts Orton’s sexual encounters as part of a gay sensibility and gay sexual appetite that defies heterosexual comprehension. The cottaging is a random, for-the-hell-of-it event and Orton still travels to Africa to please himself with the willing boys regardless of the truth portrayed in the ‘Diaries’. Good as the film is I wonder whether today it would be possible to show the sex in the context of a boring life and show how sex happens in between the washing of socks and the opening of tins of rice pudding: something the film almost achieves but not quite.

For all this, the film remains one of the most outstanding British films of the last thirty years and to see it at the brand new North Wall Arts centre was a treat. The North Wall is a seriously good venue and more power to its elbow in attracting a growing audience.

On the big screen the Moroccan sequence glows with brightness and the montage of Orton/Halliwell’s arrival at the beach in Marrakech gleefully sends up the equivalent moment in ‘Some Like It Hot’ – right down to the use of the same music. Other delights more appreciated on the big screen are the colour palette - all grim and grainy - showing the London of Orton’s cottaging expeditions and the sequences shot in the exterior of Neville Road, the rain lashing down on Paul McCartney’s Rolls Royce come to collect Orton for a discussion of the doomed screenplay, ‘Up Against It’.

A word on Lahr’s treatment of the ‘Diaries’ and Bennett’s screenplay. On the level of literary biography, Lahr’s editing of and interpretation of the Diaries need a further reinvention thirty years down the line, and the screenplay is a further barrier that needs unpicking. It may be a given that all art selects and arranges its components to best present a narrative, and from contingency derive meaning, but Bennett is complicit in Lahr’s reading of Orton’s lifestyle, even as he takes a dig at Lahr through his device of the parallelism of the ignored partner. The (in)famous cottaging orgy scene (Saturday 4 March, 1967), which is shown in the film out of its chronological order as an adjunct to Orton’s success on the night of the Evening Standard Awards, is deliberately placed in the ‘Diaries’ as a literary joke in opposition to a disastrous trip to Morocco. Morocco is meant to symbolise sexual freedom in contrast to the dangerous and squalid sexual cottaging of 1960s London. Orton jets off on a sudden holiday only to face disaster and lack of sexual achievement at every turn. He returns to a triumphantly-written orgy in a lavatory on the Holloway Road. The diary entry ends with a quip from Halliwell which is the punch-line to an extended literary joke – “It sounds as though eightpence and a bus down the Holloway Road was more interesting than £200 and a plane to Tripoli” – but that literary gag cannot be pulled off on screen, or is dropped by Bennett and Frears in favour of a story which depicts Orton’s sexual encounters as part of a gay sensibility and gay sexual appetite that defies heterosexual comprehension. The cottaging is a random, for-the-hell-of-it event and Orton still travels to Africa to please himself with the willing boys regardless of the truth portrayed in the ‘Diaries’. Good as the film is I wonder whether today it would be possible to show the sex in the context of a boring life and show how sex happens in between the washing of socks and the opening of tins of rice pudding: something the film almost achieves but not quite.

For all this, the film remains one of the most outstanding British films of the last thirty years and to see it at the brand new North Wall Arts centre was a treat. The North Wall is a seriously good venue and more power to its elbow in attracting a growing audience.